ADVERTISEMENT

The 1960s were a complicated decade for the United States military. The polarizing, drawn-out conflict in Vietnam threw soldiers, sailors, and aviators into the volatile politics and protests of the era. But there was one undisputedly heroic story from that time that has seldom been told, and all but forgotten: the role the U.S. Navy, and specifically Underwater Demolition Team frogmen, played in the celebrated Apollo space program, including the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon landing.

For even those of us who were either not alive during, or old enough to remember, the first Moon landing, the grainy footage of Neil Armstrong bouncing down the ladder of the lunar landing module, and his words—"one small step…"—are seared into our collective memory. Less familiar is the footage of the command module, suspended by massive, striped triple parachutes, descending through a hazy, tropical sky, then splashing heavily into the choppy Pacific.

To most, that was the end of the story. Pop the corks, light the cigars. Mission accomplished. And yet, there was more to be done. When the capsule holding Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, and Michael Collins splashed down, it toppled upside down in the waves. How the capsule was secured and the astronauts freed from their tiny, sealed projectile was the job of a specialized group of men who'd been pulled from the jungles of Southeast Asia and highly trained for this most complicated and specific of tasks.

The capsule landed in "Stable 2" position, in other words, upside down. It would then right itself with bladders that fill with air.

In my experience, the best stories involving a watch are those that aren't even about the watch. This is one of those stories. While another wristwatch, the Omega Speedmaster, is most commonly associated with the Moon landing and the entire American space program, there were other watches—quite a few actually—that played equally interesting supporting roles. There was John Glenn's Heuer, Scott Carpenter's Breitling, Jack Swigert's Rolex, Dave Scott's Bulova, and William Pogue's Seiko, to name a handful. Those were all "flown" watches, ones that went along for the ride, so to speak. But just as the role of the Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) swimmers in the space program has largely remained out of public view and anonymous, so too were the watches they wore—until now.

This is the Tudor 7928 once owned by UDT/SEAL Steve Jewett; who has since passed. It now resides with his family and serves a totem to his service. Jewett took part in the Apollo Capsule Recovery program.

Tudor has produced a short documentary film, called "Splashdown: The U.S. Navy's Daring Role in the Moon Missions," about these frogmen and the Apollo capsule recovery missions. Needless to say, dive watches are involved, though they're not central to the story. But as it happens, the great majority of UDT swimmers and Navy SEALs in the late 1960s were issued Tudor Submariner watches according to classified records. This will come as no surprise to longtime Hodinkee readers who might recall past projects like Moki Martin's "Talking Watches" episode and "The Long Return," both of which featured well-used Tudor Subs. Now, photographic evidence and interviews for this new film reveal that the men tasked with recovering the Apollo capsules were wearing—and using—Tudor watches.

Before diving into the specifics of this story, it's perhaps worth briefly revisiting the history of the Tudor Submariner and its military use. It's no secret that Tudor's history exists in parallel, and perhaps a bit in the shadow of, Rolex. Established in 1926 as a more affordable alternative to Rolex, Tudor, for decades, made use of The Crown's engineering and manufacturing might to combine robust, watertight cases, crowns, and crystals with third-party movements to keep prices reasonable. Often these watches resembled their Rolex siblings, to the point of almost being homages, if that word can be used. So to the Explorer, we saw the Ranger, to the Datejust, we got the Prince Oysterdate, to the Daytona, there was the "Big Block" chronograph. And the Tudor parallel to the Submariner? Well… the Submariner. Tudor's version of the diving watch debuted in 1954, shortly after Rolex's. And while some of the world's navies procured diving watches from Rolex, most notably Britain's Royal Navy, the offer of a more cost-effective but equally capable version appealed to many others, most notably the French Marine Nationale and the US Navy, which started issuing them to its divers and UDT frogmen as early as 1964.

Shanda Jewitt and Marie Jewett. Daugher and Widow of Steve Jewett.

The specific watch that the U.S. Navy issued was the reference 7928, a watch Tudor first introduced in 1959. It was the first Tudor Submariner to have crown guards and the larger 39-millimeter case diameter (up from 37mm). It remained in continuous production through 1969, with some minor tweaks to the crown guard shape and dial printing along the way, but examples were worn and saw plenty of action well past that year. Of course, Tudor has continued its connection with naval units up to this day, most notably with the Pelagos FXD, in both its blue "Marine Nationale" form and the black dialed FXD that is closely tied to the U.S. Navy.

Bill Jebb, the UDT/SEAL (top row, middle) discusses how he used his Tudor Submariner during the Splashdown Recovery development.

The Navy's maritime special operations force has its roots in the Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDUs), Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs), Amphibious Scouts and Raiders (S&R), and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Maritime Unit established during World War II. These specialized units were tasked with scouting beach approaches and clearing underwater hazards in advance of amphibious invasions, such as that on D-Day in June of 1944. These weren't necessarily fighting units, but problem solvers. They were often only equipped with swim trunks, fins, a diving mask, a watch, and a knife, and sent ashore, particularly under the cover of night, to plant explosives and destroy obstacles put in place to deter amphibious landings by the Army and Marines. By the early 1960s, the concept of commando-type, small-team operations had proven effective enough to evolve the UDT's role to include surprise attacks, often from boats or deployed from submarines. The unit existed in parallel with a new fighting force: the Navy SEALs. These teams were well suited for the unconventional, often "guerrilla" style combat that was part of the Vietnam War, and UDT and SEAL teams were routinely deployed up and down the coast and in the river deltas of Southeast Asia. By this time, according to records, most of them were wearing issued Tudor Submariners, often on rubber straps, sometimes on fabric pass-throughs, or occasionally on a custom-engraved steel Olangapo cuff.

In contrast to the highly divisive war in the 1960s, but also an element of the Cold War at large, the United States was also pursuing its ambitious space program. Started in the late '50s with the Mercury program (suborbital and later orbital flights with one astronaut), then Gemini (orbital, two men per capsule), the effort, spurred by President Kennedy's challenge, evolved to "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth." This was the Apollo program. And while the first half of that challenge was a well-told story of heroic test pilots with "the right stuff," the "return him safely" part called for a different group of heroes. The specialized skills of the UDT frogmen were well-suited for the unique challenge of harnessing a space capsule bobbing in the ocean. They were unflappable, comfortable being uncomfortable, trained for tough, aquatic work, and adaptable. For those selected to participate in the Apollo recoveries, being pulled out of jungle combat to wrangle a spacecraft in the ocean would have been jarring, but also a prestigious honor and a very unique assignment.

Bill Jebb: Former UDT/Seal, Apollo Recovery Program Development Team.

Mementos from the Apollo era, specifically the Recovery Program.

If you've only been paying attention to manned spaceflight for the past couple of decades, you'd be forgiven for thinking that returning astronauts to terra firma had more of an emphasis on the firma. Until recently, NASA farmed out astronaut transport to and from the International Space Station to Russia. As a result, capsule returns have been land-based, typically with a resounding and violent "thud." It's the way the Soviet Union chose to do things, dating back to the days of Yuri Gagarin, as opposed to the American program, which had capsules splashing down in the sea. Both methods have their risks and benefits.

Wesley T. Chesser: Former UDT/Seal | Swim #2, Apollo 11 Recovery Program.

In 1961, Mercury astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom almost drowned when the hatch blew off his Liberty Bell 7 capsule, causing it to flood with seawater. He narrowly escaped, his own spacesuit rapidly filling with water before a helicopter finally plucked him to safety. The capsule itself sank to the bottom of the ocean and was only recovered in 1999. In fact, it was this incident that prompted NASA and the Navy to enlist the support of UDT swimmers to secure capsules and deploy flotation devices. In 1965, the Soviet Union's Vokshod 2 capsule, from which cosmonaut Alexei Leonov famously performed history's first spacewalk, crash-landed in a remote part of Siberia, miles away from its intended landing site and out of radio contact. Leonov and his crewmate, Pavel Belyayev, had to survive for three days in extremely cold conditions, only to then cross-country ski nine kilometers to a helicopter landing site.

The logistics of an ocean splashdown are anything but simple. It's still astonishing to consider that NASA was able to put a spacecraft on the Moon with the technology of the era—slide-rules and banks of computers with less capability than the smartphone in your pocket now. But then to return the command module, the same one that had been orbiting the Moon, to a precise location in the vast Pacific Ocean would have involved calculating angles of re-entry, fine-tuned with thrusters, a heat shield to protect it from burning up, and the deployment of giant parachutes to slow its final fall into the water. That was all NASA's—rocket scientists'—territory. Once it hit the water, it was up to the U.S. Navy, which had been conducting recoveries since Alan Shepard's first Mercury flight in 1961 and had fine-tuned its procedures ever since.

The Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopter hovers above the capsule, with the USS Hornet, where it took off from, in the background.

The USS Hornet was the Navy's aircraft carrier tasked with the recovery of Apollo 11. It was festooned with a large banner reading, "Hornet Plus Three," alluding to the fact that its manifest would soon add Messrs. Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin. Another VIP was also aboard: President Richard Nixon was there to greet the astronauts. Since even the slightest miscalculation, equipment malfunction, or weather anomaly could send the returning capsule hundreds of miles off of its landing target, the Navy had three recovery teams on standby, with Sea King helicopters at the ready. The day before the scheduled splashdown, there was rough weather forecast in the intended landing area, so they re-routed the capsule to a new site, 240 miles away, forcing the Hornet to steam through the night to get to the correct area.

When, on July 24th, the Apollo 11 command module came through the clouds, it did so with astonishing velocity and drama. "It looked like a comet coming through the atmosphere," UDT swimmer Wesley Chesser recalls.

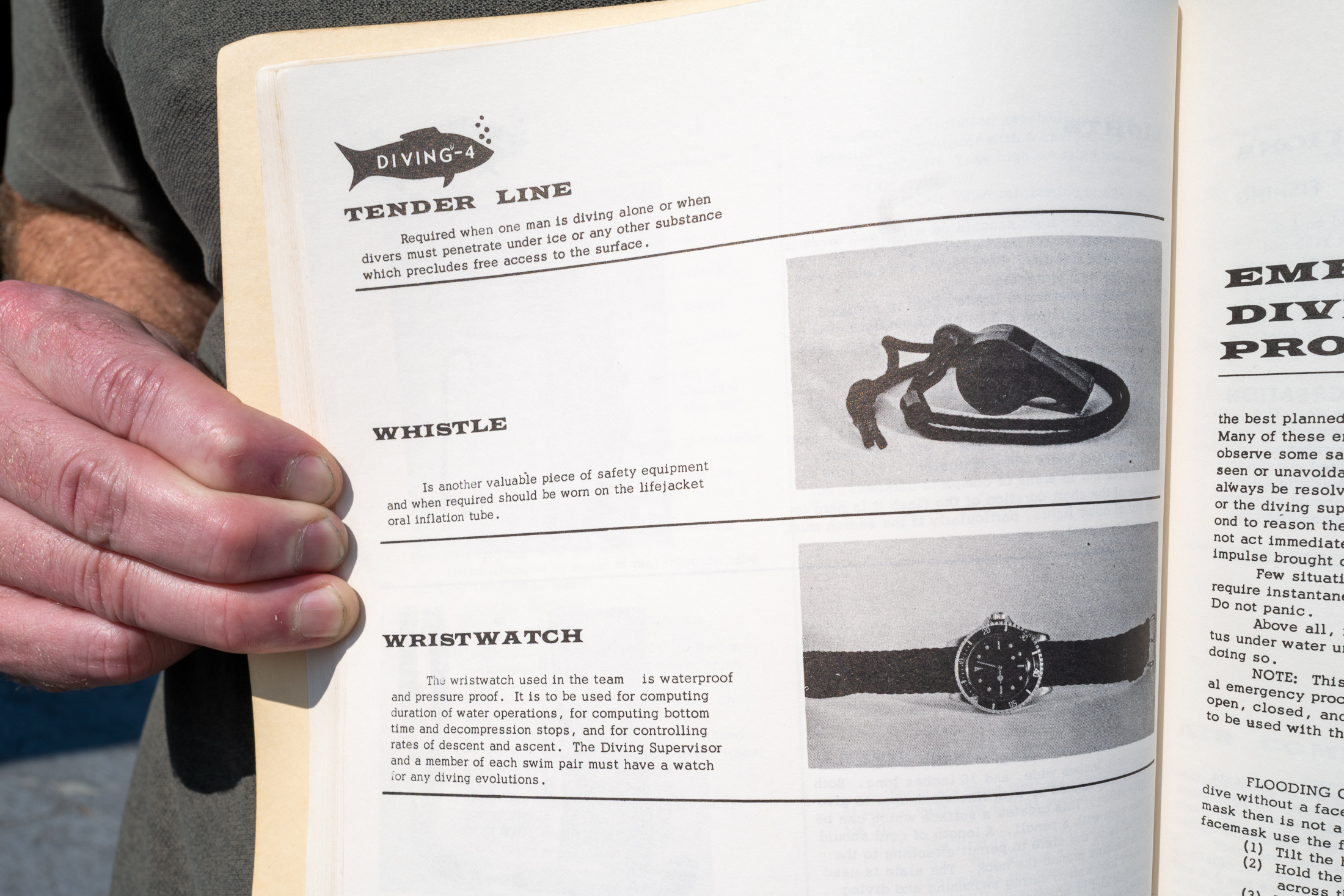

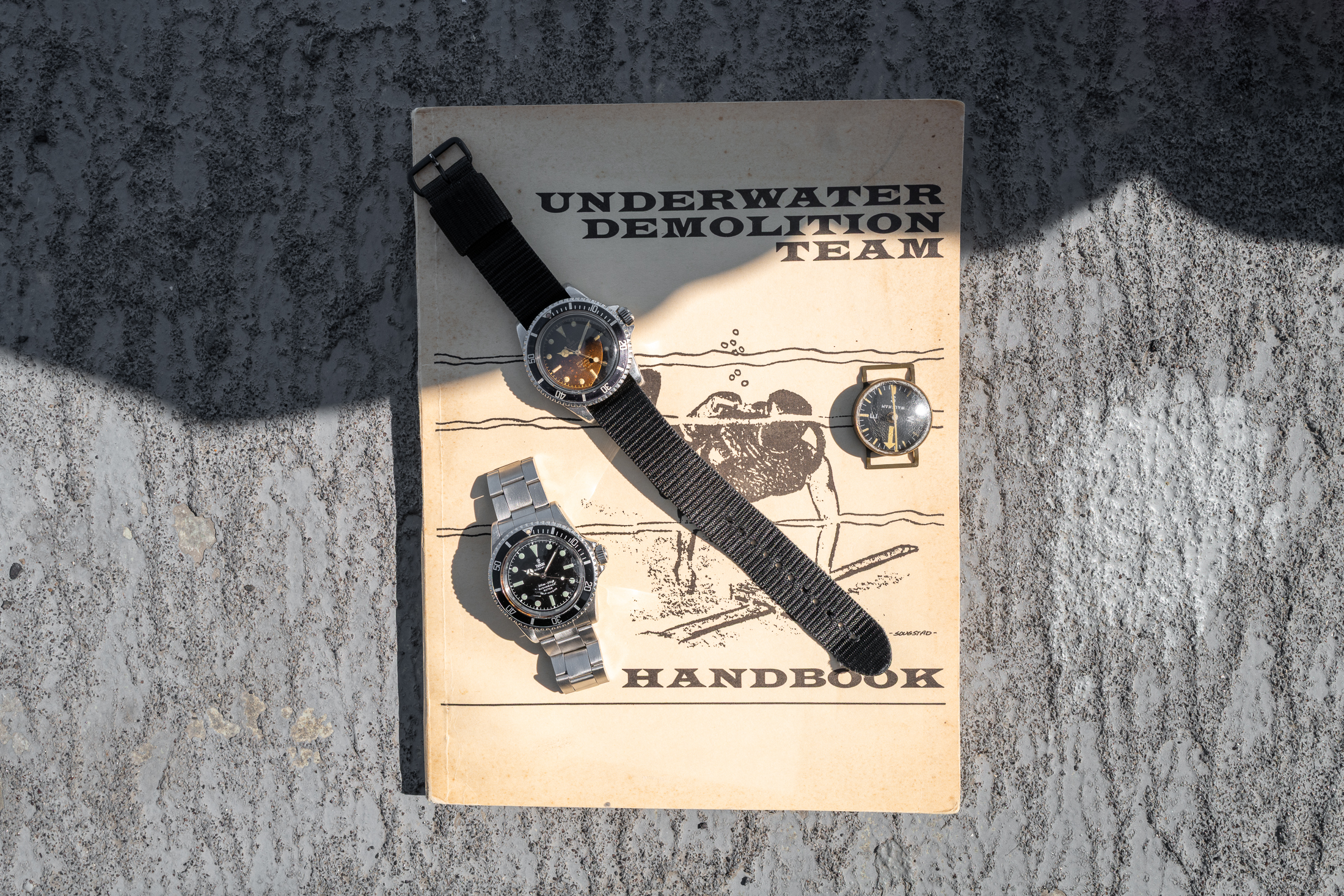

On page 85 of the official UDT manual, a Tudor dive watch is depicted within the standard issue kit

The capsule, a burning projectile, sent three sonic booms across the deck of the Hornet. Then its triple parachutes burst open, slowing its descent, and it landed with tremendous force in the waves some 12 miles downwind of the Hornet, and the well-rehearsed recovery procedure kicked into action.

With its hatch sealed shut, the capsule was watertight and could float, although its orientation depended on how it landed. Large flotation balloons on top of it inflated automatically, which slowly righted it in the water. The three astronauts inside were essentially captives until the frogmen came to extricate them. The first task of the UDT swim team was to secure the capsule so it remained upright and did not drift away. UDT swimmer John Wolfram jumped into the choppy water in full scuba gear and wetsuit, swam to the capsule, and attached a sea anchor (a type of parachute) to slow its drift. He was followed by Chesser and Michael Mallory, who worked to secure a flotation collar around the circumference, inflate it, and then position two inflatable rafts, both of which were tethered to the capsule.

From a separate helicopter, a fourth swimmer jumped into the water and climbed aboard one of the rafts, donned an awkward hazmat suit, and pulled his way to the capsule. This was Clancey Hatleburg, the decontamination specialist, and it was his job to make sure that no contaminants from the Moon would make it onboard the Hornet. He quickly opened the capsule's hatch, tossed in three hazmat suits, shut the hatch, then proceeded to spray the capsule with a decontaminant fluid (betadine) to kill anything that might have made the journey from the Moon. Then he helped the astronauts out of the capsule, into the raft, scrubbed them down with bleach using a car wash mitt, and then assisted them into the rescue netting for hoisting into the waiting helicopter for transfer to the Hornet. The astronauts were transferred onboard immediately into a specially equipped Airstream quarantine trailer, enjoying a heroes' welcome, while the frogmen secured a helicopter hoist to the capsule for extraction from the sea. Job done.

LTJG John McLachlan's Swim Team in front of the SH-3 Sea King used in the recovery efforts.

LTJG John McLachlan being interviewed aboard the USS Hornet - Sea, Air and Space Museum. The MQF, space capsule mock up, and SH-3 Sea King helicopter of the Apollo recovery program behind him.

Many of the issued examples of Tudor 7928 have seen decades of service; a little patina isn't unusual.

This procedure was carried out, with some refinement, for all of the Apollo missions, largely unseen to the public, which was also unaware of the intensive training and preparation that went into it beforehand. "While they were in space," recalls Chesser, referring to the astronauts, "we were doing rehearsal after rehearsal after rehearsal."

The UDT swimmers and entire recovery team spent weeks ahead of time practicing in all conditions, and for virtually any contingency: night splashdown, calm seas, rough seas, deep water recovery, even the presence of sharks. "When [the helo] gets low, the rotor wash creates a lot of movement in the water. That attracts sharks." Frogman John McLachlan goes on: "I remember one night, we jumped at the right time, and we were in the middle of 50 or more sharks. There was nothing to do but swim to the command module and climb up on the collar. So that was exciting." Typical frogman understatement.

By now, even casual watch enthusiasts know the story of the Omega Speedmaster's selection as the "Moonwatch" and its role in the troubled Apollo 13 mission. This is thanks in no small part to the formidable marketing and advertising of Omega, which has been buttering its bread with the NASA connection since Ed White wore one on a spacewalk in 1965. But until now, no one has really known about the dive watches worn by the UDT swimmers who recovered the Apollo capsules and extracted the astronauts. While we typically think of a dive watch as being used underwater to time a dive, they were also relied upon as overall mission timers. The Apollo capsule recoveries, and indeed the entire missions from blastoff to splashdown, were timed to the second, and the frogmen had to be aware of the schedule with equal precision. Where the role of the Speedmaster (or any other watch an astronaut might have worn on a trip to space) ended once they hit the water, the mission clock rolled on until everyone was safely back onboard the recovery ship. In contrast to the unforgiving environment of space, the ocean is equally unforgiving. One only needs to look at the fate of Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter's Breitling Cosmonaute to know that saltwater is not friendly to a handwound pilot's chronograph.

Issued 7928s sitting on top of the 1965 Underwater Demolition Team handbook.

Several of the UDT swimmers in the Tudor film attest that, upon being selected for the elite unit, they were issued a few pieces of necessary equipment, one of which was a watch. Far from what we think of them now, these watches would have been critical to their work, timing rendezvous, operations, dive times, decompression stops, explosives settings, and overall missions. "It was treated like every other important equipment you had," recalls former SEAL and Officer in Charge of capsule recoveries, William T. Jebb.

These swimmers selected for the capsule recoveries weren't given these watches specifically for this job, but would have worn them during their deployments in Vietnam, where the varied and often unmentionable tasks they performed required something sturdy, accurate, and waterproof. In most cases, according to Tudor records, these were Submariners. Several of the watches owned and worn by the UDT swimmers assigned for Apollo capsule recoveries are now in Tudor's possession and company archives. One admirer of these vintage pieces, and man who knows better than most the value of a good watch, is former Navy SEAL and bestselling author, Jack Carr, who appears in the Tudor film.

"They're really artifacts, and they've really been through it," says Carr, glancing down at his own vintage Tudor Submariner. "To me, it's really a representation of history and a life well lived."

"Splashdown: The U.S. Navy's Daring Role in the Moon Missions" is less about the capsule recovery mission itself, and more about the brave men who quietly and expertly did the job, with enough horological goodness sprinkled in to keep watch enthusiasts happy. It focuses on the human element, with interviews with former SEALs and UDT swimmers, as well as surviving relatives of UDT frogmen who participated in the Apollo recoveries. And while the movie was released to coincide with the splashdown of the Apollo 11 capsule (July 24th, 1969), it actually covers those frogmen who worked on a number of Apollo missions, all of which were successful. Like most of the best stories about watches, this one really has little to do with what was on these men's wrists. Because in the end, it's not about the watch at all. It's about what you do while wearing one.

You can watch the full documentary, "Splashdown: The U.S. Navy's Daring Role in the Moon Missions," here, and on Tudor's website.

Top Discussions

Splashdown: The Little-Known Story Of Navy Frogmen And The Space Program

Business NewsRolex Is Now Certifying Watches That Are Two Years Old In Change To CPO Rules

Hands-OnThe Albishorn Type 10 Classic – An Imaginary Vintage Pilot's Watch That Finally Exists